A mountain lion was caught on video last month roaming early one morning through an alley in Wichita, becoming the first of its species to ever make a confirmed appearance in a city in Kansas.

That sighting continued a trend in recent decades that’s brought an increased presence in the Sunflower State of some wildlife species that were previously absent or rare here.

Those animals include mountain lions, elk, black bears, river otters and armadillos, said Matt Peek, an Emporia-based wildlife research biologist for the Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism.

In addition, he said, wild turkey, Canada goose and deer populations that had been reduced significantly by hunting have gone from “very rare to very abundant” in Kansas.

Some of the comebacks involved are great success stories in terms of modern wildlife management, Peek said.

Most of the species involved saw their populations decline as a result of subsistence living and “associated unregulated harvest for food or livestock protection,” he said.

“Now that people’s actions have become favorable, they’ve rebounded,” Peek said. “In some cases, all it took was protection.”

Biologists — and perhaps even some interested members of the public — have aided the spread of some of the species involved by personally moving them around, he said.

Mountain lions and black bears

Kansas went 103 years, from 1904 to 2007, without any confirmed sightings of mountain lions.

But the state has since seen 36, including 12 last year and three this year, according to KDWPT, which protects and manages Kansas’ natural resources.

Mountain lion and black bear populations have come to thrive in states neighboring Kansas, meaning the existing habitats are largely occupied and young males there are forced to disperse into new areas in search of their own territory, Peek said.

“In the case of lions, adult toms will kill the yearling males, so in lightly hunted populations that are near carrying capacity, the young must leave or be killed,” he said. “This is what really started the movement of mountain lions into the Midwest 25 to 30 years ago, when a bunch of Midwest states that hadn’t had them for 100 years started to get a few.”

Black bears, on the other hand, have visited southwest Kansas “basically annually” over the past 20 years or so, “usually a young bear or two in the fall along the Cimarron River,” Peek said.

Bears have also become more frequent in southeast Kansas, which sees “basically several per year now, where there was basically none before,” he said.

Mountain lions and black bears still aren’t considered “resident” animals in Kansas, Peek said.

River otters, deer and wild turkeys

Some species — such as river otters, deer and wild turkeys — were depleted by unregulated hunting in the 1800s and early 1900s.

“Wildlife management became a science after they were depleted,” Peek said.

KDWPT and other agencies then reintroduced river otters and deer in Kansas “with the protections and management of modern wildlife science, and they’ve generally done well since,” he said, adding, “It’s also worth noting that most people aren’t living directly off the land now.”

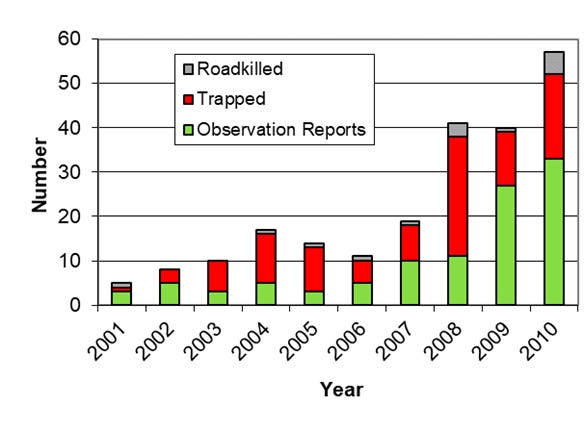

The annual number of river otters identified as being present in Kansas rose from 10 in 2003 to near 60 in 2010, according to figures compiled by determining how many had been trapped, killed by vehicles or observed in the wild.

KDWPT figures show the number of wild turkeys seen by rural mail carriers taking part in an annual spring survey rose from about one every 100 miles in 1997 to about five every 100 miles in 2007. It then fell to its current level of about two every 100 miles.

The state’s deer population managed to rebound, and that species has naturally reoccupied its historic range without having to be reintroduced there by KDWPT, Peek said. Your stories live here. Fuel your hometown passion and plug into the stories that define it.

Elk

Elk are another example of a species that has bounced back significantly in the past 20 years or so as a result of natural migration as well as their being introduced onto land at Fort Riley in the 1980s and 1990s, Peek said.

“Elk are now reproducing on private lands in several parts of the state, and they have been legally harvested from almost one-quarter of the counties in Kansas in the past five or six years,” he said.

Armadillos

The number of armadillos documented during an annual roadside survey conducted by KDWPT rose from less than 100 in 1995 throughout Kansas to more than 800 in 2003, records show.

“The increase in abundance by armadillos is likely the result of climate change,” Peek said. “Warming weather has allowed them to survive farther north than they were previously able.”

KDWPT no longer tries to count Kansas armadillos.

“They were overwhelming a survey designed for other species, so we quit keeping track of them,” Peek said.

Be the first to comment